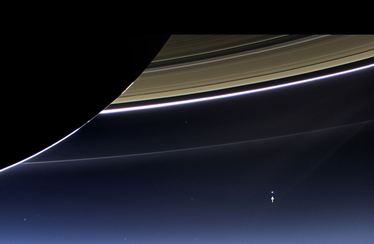

Image Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech/Space Science Institute

Image Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech/Space Science Institute But while Neil Armstrong’s one small step would summon a giant leap in the space agency’s reputation, other events would pummel its public persona in the years to come: the Apollo 1 fire, the near-crippling of Skylab and the disappearance of Americans in space for much of the 1970s, to name a few. With the bloated costs and design disappointments of the Space Shuttle—not to mention the later tragedies of Challenger and Columbia—NASA has endured a combination of severe budget cuts and diminished public support.

Yet NASA stubbornly hangs on, as if personifying that line from the cult TV show Firefly: “You can’t take the sky from me.”

At first blush, the space agency’s latest PR coup seems almost laughable. In June, NASA and the Jet Propulsion Laboratory urged people to wave at the sky on July 19 while its space probe Cassini, currently orbiting Saturn, aimed its camera toward the distant Earth. And by “distant,” I mean well over 800 million miles away.

And you thought finding your seat in a photograph of your favorite football stadium was a challenge!

Yet NASA created a deluge in news coverage and social media buzz around the “Wave at Saturn” outreach (also called, less poetically, “The First Interplanetary Photo Bomb”). While there’s no way to know how many people took part, it seems easily in the hundreds of thousands. From flash mobs in New York City to Comic-Con attendees in San Diego, people gathered to wave skyward—even in places where the planet wasn’t visible.

The payoff brought a global collective gasp: a stunning portrait of the tiny Earth and its even tinier Moon visible off the edge of Saturn’s great rings.

“The farthest any human being has ever traveled—every explorer who has climbed to a mountaintop, or dived to the deepest trench—is contained in those images,” wrote astronomy expert Phil Plait. “The farthest we humans have ever explored, to just beyond our own Moon—more than three days’ worth of travel at very high speed—is just a few pixels in these pictures.”

NASA’s seemingly silly initiative did exactly what was intended: reminding the public of its legacy and its future.

At the moment, the space agency relies on Russia to send humans into space, and then only to the International Space Station in low-Earth orbit. The manned Orion space vehicle is at least seven years away. Sending robotic rovers to Mars or sophisticated probes to the planets, while offering the occasional cool moment, leaves us feeling a little removed from it all.

And yet, NASA’s greatest triumph, landing humans on the Moon, was successful in part because all of humanity felt it had a stake in the outcome. The agency resurrected that notion with a single request: wave at Saturn. Once again, the entire planet felt it was part of the story—and was humbled by the result.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed