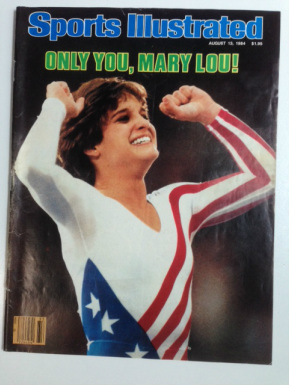

Mary Lou Retton in Sports Illustrated

Mary Lou Retton in Sports Illustrated Never before or since I have seen a news conference grow silent like that.

Every reporter in the room—scores of them from media outlets across the globe—stared at me. I had just learned a very hard, very embarrassing lesson about being prideful.

The events leading to that lesson began the previous night at the Pauley Pavilion on the campus of UCLA. American gymnast Mary Lou Retton was trailing Romanian Ecaterina Szabo in the all-around by a mere 0.15 point. Still, it would take a flawless performance by Retton in the vault or an abysmal failure by Szabo on the uneven bars to change the outcome.

Thus was the curtain lifted on one of the most remarkable moments in Olympic history.

Young Retton, just 16 years old and a pixie-ish 4-foot-9, took one last look at her coach, Romanian transplant Bela Karolyi, and launched herself down the runway toward the vault. She threw herself into her personalized take on the Tsukahara, a maneuver that entails a layout back flip with a double twist. She landed perfectly and froze, arms aloft, an enormous grin on her face. Then Retton started leaping about, hugging Karolyi and waving to the crowd, certain that she’d nailed it.

She did. Her score was a perfect 10.

Her second vault barely mattered in scoring, but it mattered to the joyful Retton. She repeated the amazing maneuver—and scored a second 10.

Mary Lou Retton was an overnight sensation, a shining example of how Americans could still fulfill their dreams. No wonder, then, that the news conference held the next day at the Main Press Center was jammed with journalists.

My friend Dick and I were there as well. As press operations volunteers, our credentials gave us access to news conferences. In addition to the many we attended at the swim venue, we managed to attend larger conferences featuring Retton and Karolyi, track and field giant Carl Lewis and distance runner Mary Decker (soon to be Mary Decker Slaney, having announced her engagement to British discus thrower Richard Slaney at the Olympic news conference).

This access was helpful. Both Dick and I were stringing for newspapers back home, so these conferences helped feed the beast. Dick’s assignment was the more rewarding and intense, filing daily reports for the Holland Sentinel with a Tandy computer and a modem so slow he could have mailed his stories faster. I was writing for a small weekly, the Portage Patriot, as well as my college paper, the Western Herald. (Although I’d finished my classes, graduation was still a month away.) I wrote my stories long-hand and dictated them over the phone.

The Retton story promised to be a highlight for both of us. We planted ourselves a few rows from the front and watched as the news conference began.

Before long, I grew puzzled by the softball questions most reporters were asking, like, “Mary Lou, how did you feel when you saw that 10 on the scoreboard?” and “Bela, when did you know she had the gold medal?”

I thought there was a deeper story to tell, how a 16-year-old girl who few Americans had ever heard of before last night was dealing with this sudden fame. Such adulation was wonderful and dangerous. It had destroyed many young lives in the past; how was she handling it now, and how would she deal with the pressures yet to come?

And why wasn’t anyone asking that question?

Finally, I looked at Dick. “I’m going to ask a question,” I whispered.

As a press operations volunteer, not a credentialed journalist, I wasn’t sure it was allowed. But I was going to do it anyway. After all, said my immature and prideful 22-year-old brain, hadn’t I won national attention for investigative reporting just months before? I’d helped expose a scheme in which universities were artificially inflating football attendance figures. I deserve to be here! I deserve to show these reporters how to be reporters!

I waltzed to the microphone, reporter’s notebook in hand, and waited my turn. It came at last. My big moment. Every reporter in the room watching me, waiting for me to bestow my journalistic wisdom upon them.

I had my question ready in my head: “Mary Lou, I imagine this is all a bit overwhelming. Days ago, you were largely unknown. Now, all that’s changed. How are you handling, and how will you keep handling, this attention, this idea that all of America wants to put you on a shelf in their homes?”

And that’s when God showed once again that He has a sense of humor.

Because the question that came out of my suddenly dry mouth went something like this: “So, um, I was wondering, um, before your gold medal, no one knew you. So how are you handling the fact that all of America would like to take you home?”

Silence. Complete, funereal silence.

I saw Retton hesitate, uncertain how to answer. I saw Karolyi’s face turn red with fury. I saw my right hand, pressing pen to notebook, tremble so much that little dark scratches appeared on the paper.

What I didn’t see was the reporter who leaned over to Dick and asked, “Who is THAT bozo?” To which my best friend, the guy who’d take a bullet for me, replied with a shrug and an expression that said, “I have no idea.”

God may be humorous, but He’s also merciful. My suffering was brief. With amazing wisdom for someone so young, Retton broke the silence by answering the question I intended to ask: “I love it. I intend to handle it well. I have to learn to live with it.”

I pretended to write down her response, nodded my thanks and slipped away, thoroughly humiliated.

I’d like to say I was never prideful again, but that would be lying. Still, it’s a lesson that’s stuck with me, even as I chuckle over it 30 years later. I hope Retton and Karolyi chuckle over it, too—or better yet, have forgotten it entirely.

Next time: The Faux-pening Ceremonies and Final Memories

RSS Feed

RSS Feed