There was no such thing as streaming video in 1984—no YouTube, no Instagram, no Internet or Web-like tools outside of the military or academia. If a reporter at the Olympics had to cover, say, weightlifting and swimming events occurring at the same time, he or she had to make a choice.

That’s where press operations came to the rescue.

After my brief and unhappy assignment in crowd control at the Olympic Swim Stadium, I landed the job I wanted most: Interview Note Taker, the same task as my friend Dick. I don’t recall what prompted the switch—maybe the French photographer lodged a complaint—but I was thrilled.

Here’s how it worked. After a medal event, the winners would gather in the press tent behind the stands. They sat at a long table while reporters and photographers congregated in front of them. To the side was a smaller table where three press operations volunteers would sit. Each was given a medal winner—one for gold, one for silver and one for bronze—and tasked with recording the quotes of that individual or team. (I’m reasonably sure we used tape recorders for accuracy, though I also took notes for backup.) When the press conference was over, the volunteer would quickly type up his or her person’s Q&A on an electric typewriter at the back of the tent, then use a fax machine to send the quotes to the Main Press Center in downtown LA. There the staff would make copies and put them on shelves, labeled by event. In that way, reporters had access to accurate quotes and results that they could include in their stories—even if they hadn’t attended the event.

This was the kind of thing I’d looked forward to doing at the Games. I was excited to think that the quotes I was typing up and faxing were helping journalists from around the world cover the Olympics. Whenever I visited the Main Press Center, I stopped by the large bank of shelves just to see copies of the Q&A documents I’d sent in previous days. That, along with writing for two newspapers back home, made me feel like a real Olympic journalist.

I wish I’d kept track of the swimmers whose quotes I gathered during the Games. Alas, I lacked that foresight. Still, I remember being in the press tent during many post-medal interviews as a note taker. Among the winners:

· Mary T. Meagher, who gained gold by setting an Olympic record in the 200-meter butterfly.

· Rowdy Gaines, earning three gold medals despite being older than 66 of his 67 competitors.

· Rick Carey, who nabbed gold in the 200-meter backstroke but was so disappointed in his performance that he hung his head during the medal ceremony and ignored the cheering crowd. The backlash was swift and ugly. Carey later apologized and went on to win two more golds.

· East Germany’s Michael Gross, nicknamed “The Albatross” because of his enormous arm stretch, who won the 100-meter butterfly with a world record in a field so fast that the top six finishers all set national records.

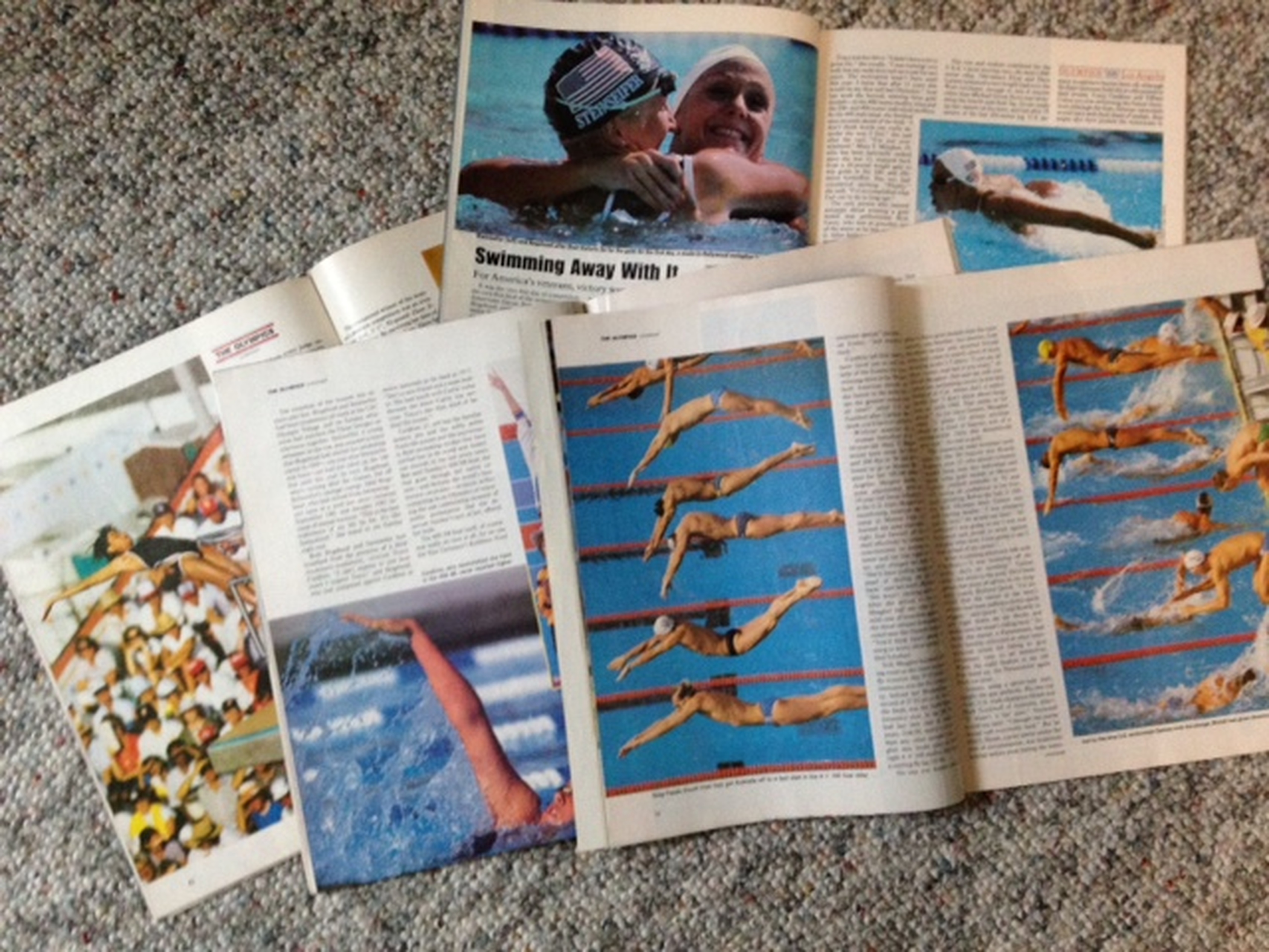

· Nancy Hogshead and Carrie Steinseifer, U.S. teammates who were the first-ever double gold medal winners in Olympic swimming history. They registered exactly the same time in the 100-meter freestyle.

· Steve Lundquist, credited his world record in the 100-meter breast stroke to inspiration and encouragement by his injured teammate, John Moffet.

· Zhou Jihong of China, a tiny (5-foot-1, 92 pounds) platform diver known for listening to piano concertos instead of rock music on her Walkman prior to dives;

· Bruce Hayes, who pulled off one of the most exciting finishes ever, with a back-and-forth in the anchor leg of the 4x100-meter freestyle against Michael Gross, earning the U.S. team a gold medal.

· Greg Louganis, whose life story is at least as powerful as his dual wins in springboard and platform diving—the first male to do so since 1928.

The reporters brought a mix of expertise. Some were familiar with the sport of swimming, others not so much. One that sticks in my mind is Craig Neff, a reporter for Sports Illustrated. I’d been reading his stuff ahead of the Games and was impressed—even more so when he took the time to counsel Dick and I on pursuing careers as journalists. He was 26 then, already a veteran of Olympics coverage, and has continued that work as recently as the London Games in 2012. I’ll always remember his kindness and encouragement.

The athletes also brought a mix of skill in dealing with journalists. Some gave thoughtful responses, even to the routine “How does it feel to win the gold?” kinds of questions. Others were clearly uneasy and kept their answers short, as if they were in a courtroom instead of a press tent. Carey, who took a bashing in the press for his near-tantrum after the 200-meter backstroke, had reason to feel uncomfortable until he offered an apology. His response to his 100-meter win, also well short of a world record, was more appreciative, and all was forgiven.

I recall a lot of questions had to do with how the swimmers prepared themselves for an event. Many talked about listening to upbeat music on their Walkman cassette players—iPods were 20 years away—or thinking about strategy, about their training, about how everything led to this moment.

And then there was Greg Louganis and his teddy bear.

Louganis was almost child-like in demeanor: quiet, quick with a smile, almost painfully shy. Not being a follower of diving, I didn’t know much about him, though most of us in press operations knew he was gay—something he would bravely recount a few years later. One thing that everyone knew in LA: He was an incredible diver.

Louganis fielded the usual “How do you prepare?” question and responded by reaching into his duffel bag to retrieve … a teddy bear.

“This is Gar,” he told the reporters. Gar was the one he hugged and spoke to before and after dives, when he wasn’t listening to Vangelis’ “Chariots of Fire” on his own Walkman.

It was a bit unorthodox, a bit unexpected, and I think Louganis stunned every person in that tent. And I’ve since decided that was his aim all along. Louganis wasn’t above shaking up the media just as he rattled his competitors.

I continued with my note-taking through the swimming and diving events, then on to synchronized swimming. The latter drew great ridicule from me at the time, but I later came to realize the intense training and physical ability it requires.

My horizons were being broadened in other ways, too. Soon I would firmly grasp the job of Olympic journalist—and experience what remains one of my most embarrassing moments.

Next Time: How I Accidentally Propositioned an Olympic Champion

RSS Feed

RSS Feed